Jared Rosenthal - Health Street Founder & CEO

Founder and CEO

Biography

Known For

Born

Education

Bachelor's Degree from the University of Michigan (1991).

Biography

The origins of me I was born in NYC, but my family moved out to central Jersey while I was still a baby. I was raised in the heart of Springsteen country in a town of displaced Brooklynites. Every dad in my town commuted to the city five days a week, coming home late in the evening in carpools, the train, or the dreaded, life-draining bus. I had a great childhood, but I swore to myself early on that I would never commute a day in my life.

When I was young and my father was still building his own law practice, he would close it down for the summer, and my family would all go south to Wildwood, NJ, to live on the boardwalk in the back of my grandparents' penny arcade. It was nothing short of heaven. My parents ran the wheel, the kind where you put down a quarter and hope it lands on your choice to win a teddy bear. My grandfather was the expert mechanic in charge of all the machines in the arcade, and my grandma ran the prize desk and cash register with a firm hand. Me and my sister walked around with coin belts and made change for the customers, once we were old enough.

At first, it was the magical, pre-digital age of boardwalk games. We had an amazing mechanical elephant that gave kids a ride for a dime. We had the fortune teller - just like the one in the movie Big. And we had the motion picture machine that was made up of a thousand black and white still photos; you cranked it by hand to see what happens. In the salty ocean air, I was surrounded by my family's entrepreneurial instincts; on the boardwalk, I tasted freedom - the kind that suburban life just couldn't provide a kid.

Career My business career began in 7th grade, when I formed my first entity. I sent away for a book that listed the home addresses of retired baseball players. I spent hours writing letters to my favorite stars, asking for 5 autographs each, and enclosing a self-addressed stamped envelope. Stamps were 20 cents each, so it cost me 40 cents per player, and I tried to sell each autograph I obtained for a quarter, hoping to make $1.25. It didn't work out so well. Nevertheless, I was bit by the bug of running my own business, and it never left me.

During college I started a driveway business called Jersey Driveway. That one worked. I would tar and patch driveways all day, take a long shower, and distribute flyers all evening. In six months after graduation, I made enough money to travel around the world for the next six months. In all honesty, it wasn't that much money and it was a pretty frugal trip. I think I spent $10/day for the most part, especially in Asia. But it was awesome.

When I was traveling that year after college, my need to make a difference in the world crystallized in my mind. I realized that I had to somehow combine my desire for entrepreneurship with my need to have a purpose in life. I understood that as a grown up, my business pursuits could no longer be just a way to make money; I realized that my choice of career would define me in fundamental ways, and I wanted to do great things for people. But my passion was business, not public service. So I racked my brains for months to figure out the best way to combine both.

One day it just hit me: I decided on healthcare. The healthcare system in the USA was broken in virtually the exact same way in 1992 that it is broken today. Millions of uninsured. Costs spiraling out of control. Insurance companies making medical decisions that infuriated doctors and patients. The problems seemed almost insurmountable, but ripe for people-focused innovation. And just then, I discovered a corner of the market that was in its infancy, and I realized that was my spot. I decided I wanted to work with the poor, in one of the newly formed not-for-profit "Medicaid Managed Care" companies.

The problems facing the poor in our healthcare system were so immense, and the challenges so unique, that in my idealistic, theoretical mind, I knew I could make a difference. I set up 4 interviews in one spring day in the heart of what was then the poorest congressional district in the USA. The South Bronx. I put on a suit and hopped on the subway headed north from Manhattan. Everyone else that was wearing a suit got off by 96th street. I kept going.

I emerged from the train and I will never forget the rubble I discovered all around me. In 1994, the Bronx was in ruins. The murder rate was cresting. The crack epidemic was raging. And though my heart was beating hard because I knew that I looked so completely out of place, I also knew right away that I found my purpose, and my new home base.

I landed an analyst job at The Bronx Health Plan, and 5 years later, when the chief marketing officer resigned, I talked my way into taking over his department. I inherited 35 street reps, a driver, and - though I didn't know it at the time - an RV that would change the course of my career. The 35 street reps worked in 30 different locations. They were street smart and slick. They made their own schedules. I was chasing them all over the Bronx to try and find out if any of them actually did any work. It was a mess, and I had no idea how to manage them.

One day, the RV driver, Rawle Nichols, came to me and said we should get a fleet. I thought he was crazy. But nevertheless, I asked him where he was going to be parking that day, and I surreptitiously showed up. I hid in my car and watched the RV and a team of 5 reps and a supervisor work the corner of 181st Street and St. Nicholas Avenue in Washington Heights. Something clicked. I could manage this, I could replicate this, I could scale this.

I worked up some spreadsheets and convinced the CFO that we could quadruple our growth through RV marketing, and the next day Rawle and I shot up to Rhode Island to buy 3 more used RVs. We drove them back to the Bronx and dropped them off at a young trio of graffiti artists called Tats Cru. They painted them with spray paint and we hit the streets. 12 months later, the company was growing fast. The Bronx Health Plan grew to cover all of NYC and Long Island, changed it's name to Affinity Health Plan, and this time it was easy to talk the CFO into buying 10 more RVs.

I put RVs and teams of reps in virtually every community in NYC, and hired people of every ethnicity to get out on the streets of their own neighborhoods to educate their neighbors about government sponsored health insurance - in their own language and in a way that was sensitive to their cultural needs.

From the Russian community of Brighton Beach to the Dominican community in Washington Heights, the Chinese neighborhoods of Flushing and Sunset Park to the West Indian community in Flatbush, my company and my staff thrived. And most importantly, we successfully enrolled over a hundred thousand uninsured, low-income kids and adults into a comprehensive healthcare program.

Soon, I was managing 400 staff. I discovered that developing people had its own rewards. I nurtured my best street reps, like Rhonda Morris and Rosemary Aponte; they grew to become managers and then directors and took on whole regions. I found the diamonds in the rough, I believed in them, and gave them the tools to grow. The receptionist, Evelyn Rodriguez, grew step by step into a customer rep, a senior rep, then supervisor, then manager, then director of a call center that grew from 10 to 75 staff who spoke more than a dozen languages.

Rawle became the transportation supervisor, then the manager, then the director of 25 drivers, 63 vehicles, and a warehouse. The company grew 500% in the span of a few years. I ran marketing, customer service, the fleet, and all of the company's enrollment functions. It was heady, exciting times. I was doing the right thing for my staff and making a difference for the community we served.

In 2004, I caught the attention of a recruiter. She told me about a job as VP of Marketing for a similar company, Amerigroup, in their Chicago subsidiary. Amerigroup was just like Affinity, but completely different. It was founded by a guy named Jeff McWaters, and it was for-profit, recently having become listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Whereas the executives of Affinity were making decent paychecks in a community-oriented non-profit environment while putting the profits back into the community healthcare system, McWaters had venture capital backers and made millions going public; his executive team was highly motivated to grow. I landed the job, but I felt it would have been like going backwards in time to the days when I first took over marketing in the Bronx. Did I really want to do it all over again, in a smaller city, just to make a few extra bucks? Plus, I was ambiguous about for-profit healthcare. I turned them down.

Moments later, McWaters, still the CEO of the parent company in Virginia Beach, VA, with 10 markets now under him, called me himself. I couldn't believe the words he was saying: he offered me the job of CEO of Amerigroup Illinois. I was shocked; I hadn't even considered that job. I had only been discussing Marketing until that point. I knew - before I even hung up the phone - that there was no way I could turn him down. A month later, I moved my family to Chicago.

In my first week in Chicago, I stood up in front of a surly group of my 80+ new employees. They told me everything that was wrong with the company: the members hate us, the doctors hate us, the hospitals hate us, the state government (which provided 100% of the funding) hates us, and we, the staff, aren't too pleased with the company either. (Damn. Nobody mentioned any of this during my battery of interviews!) And on top of all that, they were highly skeptical of New Yorkers, and they weren't afraid to tell me. One kinder woman stood up and said, "You look too young to be CEO. You must be very smart." Ken, the marketing manager, retorted, "Either Jared's very smart or McWaters is very dumb."

I set about turning around the company. I got rid of half of the management team. I met with government regulators, state senators, and even the governor. I hired 50 new reps. And of course, I bought RVs. 4 of them. Tats Cru painted them. The company began growing. I relocated Rawle out to Chicago to lead the transportation unit. I was charming the corporate executives in the Virginia Beach headquarters, and they called upon me to help them initiate and roll out RVs in all 10 markets across the nation. Soon there were RVs in Atlanta, Houston, Dallas, Miami, Tampa, Orlando…it was pretty amazing. Tats Cru painted them all. We had a model that worked, and it kept on working.

One day in the spring of 2005, when I had been running Chicago for Amerigroup for about 9 months, I got a call from a reporter to ask for comments on the "Cleveland Tyson case". I was blissfully unaware of it at the time, but it was about to derail my vision for multiplying our market share in Illinois. Tyson had been an Amerigroup VP who left the company 3 years before I had even heard of Amerigroup. Yet the things he claimed he observed, and the whistle blower lawsuit he filed 2 years before I took the job as CEO, would indirectly but ultimately lead to the closure of my subsidiary of the company.

When I took the job, I knew nothing about Tyson's allegations. But even if I did, people sue big companies all the time. Furthermore, I saw none of the illegal marketing practices that he alleged in his lawsuit occurring when I took the helm of Amerigroup Illinois, nor any indication that those things had gone on in the recent past. The corporate folks kept me out of the legal battle, since it didn't concern me or pertain to the current operations. But when the state attorney general joined the case, and later, US Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald, it was hard to continue growing the business in light of that huge distraction.

First, the state cut our rates, and I had the distinctly unpleasant duty of walking into a room and laying off 90 people. Not fun. But the 63 remaining staff and I held on for another year, until it finally became untenable. McWaters reluctantly decided to shut it down, and I laid off everyone else who was unable to relocate to another market. Shutting off the lights on the last night in Chicago was surreal. (Amerigroup later settled the case and admitted no wrongdoing).

Rawle and I, and our families, moved back to New York, and he went on to run the national fleet for Amerigroup. He's still there. I decided to move on shortly thereafter, and quickly proceeded to blow my life savings attempting to build a sports competition website. By December 2008, I stuck my tail between my legs and went back to get a "real" job. It was a good job: Chief Operating Officer of a six clinic occupational health system. Naturally, I bought a mobile medical unit and launched their street operations. But the glory days were fresh in my rear view mirror, and I couldn't recapture the magic of my prior jobs. I soon had a falling out my boss, and 2 weeks shy of my fortieth birthday in December 2009, I was out of a job, nearly broke, and totally dazed.

Entrepreneurship is in my DNA Maybe it was ingrained in my soul from the time I spent childhood summers working in my grandparents' arcade. Even at the peak of my professional career, I can honestly say that not a single day had gone by without me dreaming of doing my own thing. As I sat there smarting and nearing 40, I reminisced about Jersey Driveway, my business from just after college. At 21, I had been a solo operator, working with my hands, building a business from scratch. I wore what I wanted. I attended no meetings. I earned an honest dollar for a hard days work. I wanted that feeling back so bad. Why did I ever detour into the corporate world, I wondered.

A few months worth of introspection later, I bought a used RV of my own and launched Health Street. Despite having bought and managed dozens of RV's for other companies, I had never gotten behind the wheel. Rawle set up cones in a Home Depot parking lot and taught me the finer points of driving the truck. I painted it myself, and got a big sticker of a cup of pee for the sides, to advertise the drug testing. I learned from my most recent entrepreneurial failure to run things as lean as possible until I could establish a revenue stream. With just a laptop, cell phone, and mobile internet hotspot, I hit the road on the cheap, and never looked back.

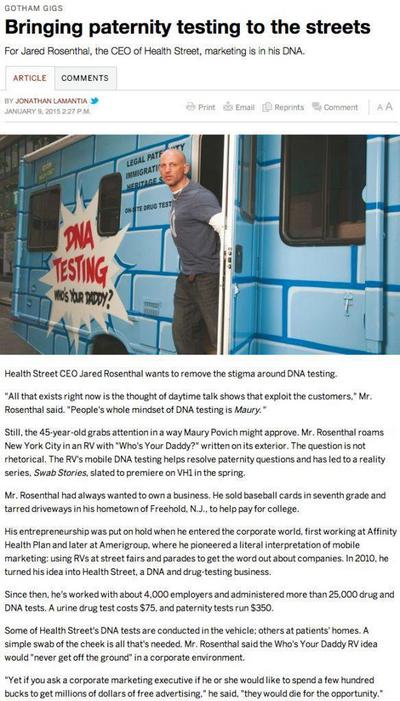

The origins of the Who's Your Daddy DNA testing truck In 2012, Health Street was cruising along, and Rawle was pushing me to finally get the RV painted right. The RV had become known around town as the pee-mobile, due to the specimen sticker. Around that time, a close friend of mine got a message on FaceBook from an 18 year old woman who said she and been looking for him his entire life. I was already working with labs, so I figured out how to set up a DNA test for him to determine paternity. I realized, if this is happening with my close friends, there might be a bigger need out there than people realize. I decided to remove the incredibly unsuccessful drug test branding and begin marketing DNA testing.

By then, I had five staff, and I held a contest to determine the slogan. I suggested "Who's Your Daddy". I was outvoted 5 to 1. I wanted to do it anyway. I had a few sleepless nights about it. Would it be offensive? Would it be too provocative? I had spent my entire career working with communities and trying to improve things out on the streets. The last thing I wanted to do was to upset anyone. In the end, I went with my gut. I could always repaint it if things went seriously wrong, I told myself. I drove the RV over to Tats Cru in the Hunts Point section of the Bronx, and told them I wanted the slogan "Who's Your Daddy" on the side.

The first time I rolled out with the truck, it was downright amazing. People were hanging out of their windows snapping photos. People laughed, gawked, cat-called, and cracked jokes all day long. Most people would yell out a neighborhood name, and say, come to x-y-z neighborhood, you'll make a killing. The stereotypes that people had about who needs paternity testing was on full display, and it was driven from what they had seen on the daytime talk shows. Nevertheless, I was dumbstruck at the totality of the response to the truck. It turned heads of every ethnicity and nationality from Rockefeller Center to downtown Brooklyn, and everywhere in between.

I parked in every neighborhood I could find, determined to not fall into the trap that all the cat-callers espoused, and committed to not perpetuating the stereotypes that people had about who needs these tests. In fact, I did my first DNA test on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and I had to tell the multi-millionaire owner of a beautiful townhouse that he was not the father of his wife's infant. I proved that the need for DNA testing is not the sole purview of lower income groups or of certain ethnicities or neighborhoods. I chose my destinations based solely on what I was in the mood to eat for lunch. Then, I made the mistake of parking the RV in Harlem. The reaction was fast and furious.

I have my hot spots to park in every nook and cranny of the city. On this day, with my adrenaline pumping over the excitement that the new RV branding was generating, I thoughtlessly chose one of those corners in Upper Manhattan. An elderly lady came right over and began berating me. She felt I was specifically and only targeting Harlem; she thought the slogan was insulting; she saw me as an interloper. I did my best to explain. I am not targeting this block - I go everywhere. I am not the enemy - I am on your side. I am not prejudging the neighborhood - I am fighting against stereotypes. I don't only come here - the RV moves around.

But it didn't matter. She saw me as part of a historical trend of exploitation of her community. I respected her wishes and left. I was shaken. It's one thing when someone accuses you of doing something wrong, but its another altogether when you are accused of just the thing that you have been opposed to your entire life. It spins you around and makes you examine yourself with a microscope.

Just then, I got approached by an African American newscaster who thanked me. She told me that by putting Who's Your Daddy on the truck, it makes the issue less taboo. She told me that she had grown up not knowing who her father was; as an adult, when she started appearing on television, a man claiming to be her dad came out of nowhere and wanted to be a part of her life. She told him, come on, let's take a paternity test before we develop a relationship. It turned out that he was, in fact, her biological father. And then, she told him to go back to where he came from; he was not welcome in her life, or in the life of his grandsons.

She told me she felt shame growing up, because she could not answer the question of who her father was. She felt the Who's Your Daddy Truck helped people like her come out of the closet and deal with their particular family issues in a less secretive fashion. And then she used the word that my clients have told me more often than any other word: the Who's Your Daddy truck offers "closure". For the people that actually need DNA tests, people like this newscaster, what they desire more than anything else is to finally answer questions that have been unresolved for years, decades, or a lifetime. These are my clients, and they have been overwhelmingly appreciative of the fact that I caught their attention with the truck.

The origins of Swab Stories In August 2012, the NY Post ran a great article about the Who's Your Daddy truck. Within hours, I was on CBS news, FOX, ABC, WPIX. Segments ran nationally on the nightly news. I did a five minute interview with Brooke Baldwin on CNN. I told some crazy stories about the emotional drama that occurs when I go out and do tests. The production companies and networks started calling. First it was a trickle, then it was a flood. In the end, 30 companies approached me about doing a reality show. At first, I was highly skeptical. I didn't trust any of them. I refused to let them exploit my clients for entertainment purposes like a daytime talk show. I doubted if they would even find a single client to appear on TV, since my clients considered their situations incredibly private.

I flew out to LA and met with a few of the companies that seemed more trustworthy than the others. I hired a lawyer. And in the end, I went with my gut, and signed on with a man I felt I could trust, Seanbaker Carter. We saw eye to eye on the vision for the show, and he convinced me that he had the professionalism to pull it off with integrity. A few months later, I grabbed Rawle and Ana Lopez, my medical technician, and we shot the 3 minute trailer. It showed the drama and intensity of DNA testing, the energy of the urban environment we work on, and the respect we have for our clients. It was not exploitative; it was respectful and dignified, but highly watchable just the same. Baker sold it to VH1, and we were off and running.

Giving life-changing news to clients There is perhaps no more important role in my job than providing results. When someone is questioning a primary relationship in their life, and perhaps had buried that question deep in their soul for years or decades, the results moment can make or break them. In that moment, the way in which I give the news can affect how they receive it and interpret, perhaps for the rest of their lives. I know who the most important person in the room is when I am giving results, whether or not the cameras are rolling, and it's never me.

What is family? Does DNA matter? Beyond the business, and beyond the show, a deeper question emerges from doing this job. What defines a family relationship anyway? I know amazing adoptive parents and terrible biological ones. I have true friends like Rawle that I think of as brothers, and I know people who don't even talk to their siblings. Why is it that we are all, still, so enamored and intrigued with the definitiveness that a blood relationship provides? I have done thousands of DNA tests. And I try to have good advice for people, if and when they are hurting. But as for me, do I believe that blood is truly thicker than water? It might be, but family is thicker than blood.

Recent articles

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/16/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/9/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/2/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/1/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/31/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/30/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/29/2024

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/20/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/17/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/16/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/15/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/14/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/13/2023

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/15/2022

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/16/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/13/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/15/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/13/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/9/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/10/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/6/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/5/2021

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/3/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/2/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/1/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 8/28/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 8/16/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/22/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/15/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/4/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/18/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/14/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/6/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/19/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/2/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/25/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/14/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/1/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/29/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/9/2020

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/6/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/2/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/17/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/4/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/4/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/8/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/27/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/29/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/28/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/13/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/30/2019

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/22/2017

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 8/31/2017

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/5/2016

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/5/2016

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/18/2016

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/22/2016

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/30/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/17/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 4/30/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/3/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/28/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/9/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/8/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/8/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/6/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/6/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/6/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 1/5/2015

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 12/30/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 12/11/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/25/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/6/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/30/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/23/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/23/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/17/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/8/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 3/7/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 2/6/2014

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 12/9/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 12/3/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/29/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/20/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/8/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 11/1/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/24/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/23/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/22/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/22/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/18/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/18/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/16/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/14/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/7/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/6/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/2/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/2/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/23/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/18/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/18/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/9/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/26/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/25/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/16/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/15/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 7/2/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/22/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 6/14/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 5/14/2013

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 10/16/2012

Written by Jared Rosenthal

Published on 9/15/2012